Step 10: in un libro

It's an election hall of idiots, for idiots, and by idiots, and it works marvelously. This is the true nature of democracy and of all distributed governance. At the close of the curtain, by the choice of the citizens, the swarm takes the queen and thunders off in the direction indicated by mob vote. The queen who follows, does so humbly. If she could think, she would remember that she is but a mere peasant girl, blood sister of the very nurse bee instructed (by whom?) to select her larva, an ordinary larva, and raise it on a diet of royal jelly, transforming Cinderella into the queen. By what karma is the larva for a princess chosen? And who chooses the chooser?

"The hive chooses," is the disarming answer of William Morton Wheeler, a natural philosopher and entomologist of the old school, who founded the field of social insects. Writing in a bombshell of an essay in 1911 ("The Ant Colony as an Organism" in the Journal of Morphology), Wheeler claimed that

an insect colony was not merely the analog of an organism, it is indeed an organism, in every important and scientific sense of the word. He wrote: "Like a cell or the person, it behaves as a unitary whole, maintaining its identity in space, resisting dissolution...neither a thing nor a concept, but a continual flux or process."

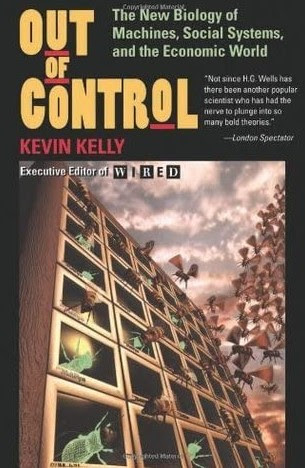

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 27)

The man's word-blindness degenerated to a complete aphasia of both speech and writing by the time of his death four years later. Of course, in the autopsy, there were two lesions: an old one near the occipital (visual) lobe and a newer one probably near the speech center.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 35)

Although it may strike us as obvious now, it took a long while for the world's best inventors to transpose even the simplest automatic circuit such as a feedback loop into the realm of electronics. The reason for the long delay was that from the moment of its discovery electricity was seen primarily as power and not as communication. The dawning distinction of the two-faced nature of the spark was acknowledged among leading German electrical engineers of the last century as the split between the techniques of strong current and the techniques of weak current. The amount of energy needed to send a signal is so astoundingly small that electricity had to be reimagined as something altogether different from power. In the camp of the wild-eyed German signalists, electricity was a sibling to the speaking mouth and the writing hand. The inventors (we would call them hackers now) of weak current technology brought forth perhaps the least precedented invention of all time-the telegraph. With this device human communication rode on invisible particles of lightning. Our entire society was reimagined because of this wondrous miracle's descendants.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 156)

The ancient Chinese on the other hand, although they never got beyond the south-pointing cart, had the right no-mind about control. Listen to these most modern words from the hand of the mystical pundit Lao Tzu, writing in the Tao Teh King 2,600 years ago:

Intelligent control appears as uncontrol or freedom.

And for that reason it is genuinely intelligent control.

Unintelligent control appears as external domination.

And for that reason it is really unintelligent control.

Intelligent control exerts influence without appearing to do so.

Unintelligent control tries to influence by making a show of force.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 169)

In Weiser's vision of an intelligent office, ubiquitous smart things form a hierarchy. At bottom, an army of microorganisms act as a background sensory net for the room. They feed location and usage information directly to the upper levels. These frontline soldiers are cheap, disposable small fry attached to writing pads, booklets, and smart Post-it notes. You buy them by the dozen-like pads of paper or RAM chips. They work best massed into a mob. [...] Every room becomes an environment of computation. The adaptive nature of computers recedes into the background until it is nearly invisible and ubiquitous. "The most profound technologies are those that disappear," says Weiser. "They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it." The technology of writing descended from elite status, steadily lowering itself out of our consciousness altogether until we now hardly notice words scribbled everywhere from logos stamped on fruit to movie subtitles. Motors began as huge noble beasts; they have since evaporated into micro-things fused (and forgotten) in most mechanical devices. George Gilder, writing in Microcosm, says, "The development of computers can be seen as the process of collapse. One component after another, once well above the surface of the microcosm, falls into the invisible sphere, and is never again seen clearly by the naked eye." The adaptive technologies that computers bring us started out as huge, conspicuous, and centralized. But as chips, motors, and sensors collapse into the invisible realms, their flexibility lingers as a distributed environment. The materials evaporate, leaving only their collective behavior. We interact with the collective behavior-the superorganism, the ecology-so that the room as a whole becomes an adaptive cocoon.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, pp. 219-220)

Not only would rooms and halls have embedded intelligence and ecological fluidity but entire streets, malls, and towns. Weiser uses the example of words. Writing, he says, is a technology that is ubiquitously embedded into our environment. Writing is everywhere, urban and suburban, passively waiting to be read. Now imagine, Weiser suggests, computation and connection embedded into the built environment to the same degree. Street signs would communicate to car navigation systems or a map in your hands (when street names change, all maps change too). Streetlights in a parking lot would flick on ahead of you in anticipation of your walk. Point to a billboard properly, and it would send you more information on its advertised product and let its sponsor know what part of the street most of the queries

came from. The environment becomes animated, responsive, and adaptable. It responds not only to you but to all the other agents plugged in at the time.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 222)

The hottest frontier right now in software design is the move to objectoriented software. Object-oriented programming (OOP) is relatively decentralized and modular software. The pieces of an OOP retain an integrity as a standalone unit; they can be combined with other OOP pieces into a decomposable hierarchy of instructions. An "object" limits the damage a bug can make. Rather than blowing up the whole program, OOP effectively isolates the function into a manageable unit so that a broken object won't disrupt the whole program; it can be swapped for a new one just like an old brake pad on a car can be swapped for a better one. Vendors can buy and sell libraries of prefabricated "objects" which other software developers can buy and reassemble into large, powerful programs very quickly, instead of writing huge new programs line by line. When it comes time to update the massive OOP, all you have to do is add upgraded or new objects.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 252)

Ted Kaehler invents new kinds of software languages for his living. He was an early pioneer of object-oriented languages, a codeveloper of SmallTalk and HyperCard. He's now working on a "direct manipulation" language for Apple Computers. When I asked him about zero-defect software at Apple he waved it off. "I think it is possible to make zero defects in production software, say if you are writing yet another database program. Anywhere you really understand what you are doing, you can do it without defects." [...]

Ted Kaehler invents new kinds of software languages for his living. He was an early pioneer of object-oriented languages, a codeveloper of SmallTalk and HyperCard. He's now working on a "direct manipulation" language for Apple Computers. When I asked him about zero-defect software at Apple he waved it off. "I think it is possible to make zero defects in production software, say if you are writing yet another database program. Anywhere you really understand what you are doing, you can do it without defects."

Ted would never get along in a Japanese software mill. He says, "A good programmer can take anything known, any regularity, and cleverly reduce it in size. In creative programming then, anything completely understood disappears. So you are left writing down what you don't know....So, yeah, you can make zero-defect software, but by writing a program that may be thousands of lines longer than it needs to be."

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, pp. 253-254)

The Method tickled my curiosity and distracted me from my writing. Was it widely known among travelers and librarians? I was prepared for the probability that others must have uncovered it in the past. Returning to the university library (finite and catalogued), I searched for a book with an answer. I bounced from index to footnote, from footnote to book, landing far from where I began. What I found amazed me. The truth seemed farfetched: Scientists believe the Method has saturated our world since time immemorial. It was not invented by man; by God perhaps. The Method is a variety of what we now call evolution.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 327)

Dawkins hoped to traverse a library of tree shapes by artificial selection and breeding. A form was born in Biomorph Land as a line so short it was a dot. Dawkins's program generated eight offspring of the dot, much as Sims's later program would do. The dot's children varied in length depending on what value the random mutation assigned. The computer projected each offspring, plus the parent, in a nine-square display. In the now familiar style of selective breeding Dawkins selected the most pleasing form (his choice) and evolved a succession of ever more complex variant forms. By the seventh generation, offspring were accelerating in filigreed detail.

That was Dawkins's hope as he began writing the code in BASIC. If he was lucky in his programming he'd get a universe of wonderfully diverse branching trees.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 332)

In the end, breeding a useful thing becomes almost as miraculous as creating one. Richard Dawkins echoes this when he asserts that "effective searching procedures become, when the search-space is sufficiently large, indistinguishable from true creativity." In the library of all possible books, finding a particular book is equivalent to writing it.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 348)

Human history is a story of cultural takeover. As societies develop, their collective skill of learning and teaching steadily expropriates similar memory and skills transmitted by human biology.

In this view-which is a rather old idea-each step of cultural learning won by early humankind (fire, hammer, writing) prepared a "possibility space" that allowed human minds and bodies to shift so that some of what it once did biologically would afterwards be done culturally. Over time the biology of humans became dependent on the culture of humans, and more supportive of further culturalization, since culture assumed some of biology's work. Every additional week a child was reared by culture (grandparent's wisdom) instead of by animal instinct gave human biology another chance to irrevocably transfer that duty to further cultural rearing.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 443)

This book is based on my astonishment that nature and machines work at all. I wrote it by trying to explain my amazement to the reader. When I came to something I didn't understand, I wrestled with it, researched, or read until I did, and then started writing again until I came to the next question I couldn't readily answer. Then I'd do the cycle again, round and round. Eventually I would come to a question that stopped me from writing further. Either no one had an answer, or they provided the stock response and would not see my perplexity at all. These halting questions never seemed weighty at first encounter-just a question that seems to lead to nowhere for now. But in fact they are protoanomalies. Like Hofstadter's unappreciated astonishment at our mind's ability to categorize objects before we recognize them, out of these quiet riddles will come future insight, and perhaps revolutionary understanding, and eventually recognition that we must explain them.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 563)

For one thing, it was easy to get lost. Without the centering hold of a narrative, everything in a hypertext network seems to have equal weight and appears to be the same wherever you go, as if the space were a suburban sprawl. The problem of locating items in a network is substantial. It harks back to the days of early writing when texts in a 14th-century scriptorium were difficult to locate since they lacked cataloguing, indexes, or tables of contents. The advantages which the hypertext model offers over the web of oral tradition is that the former can be indexed and catalogued. An index is an alternative way to read a printed text, but it is only one of many ways to read a hypertext. In a sufficiently large library of information without physical form-as future electronic libraries promise to be-the lack of simple but psychologically vital clues, such as knowing how much of the total you've read or roughly how many ways it can be read, is debilitating.

Hypertext creates it own possibility space. As Jay David Bolter writes in his outstanding, but little known book, Writing Spaces:

In this late age of print, writers and readers still conceive of all texts, of text itself, as located in the space of a printed book. The conceptual space of a printed book is one in which writing is stable, monumental, and controlled exclusively by the author. It is the space defined by perfect printed volumes that exist in thousands of identical copies. The conceptual space of electronic writing, on the other hand, is characterized by fluidity and an interactive relationship between writer and reader.

Technology, particularly the technology of knowledge, shapes our thought. The possibility space created by each technology permits certain kinds of thinking and discourages others. A blackboard encourages repeated modification, erasure, casual thinking, spontaneity. A quill pen on writing paper demands care, attention to grammar, tidiness, controlled thinking. A printed page solicits rewritten drafts, proofing, introspection, editing. Hypertext, on the other hand, stimulates yet another way of thinking: telegraphic, modular, nonlinear, malleable, cooperative. As Brian Eno, the musician, wrote of Bolter's work, "[Bolter's thesis] is that the way we organize our writing space is the way we come to organize our thoughts, and in time becomes the way which we think the world itself must be organized."

The space of knowledge in ancient times was a dynamic oral tradition. By the grammar of rhetoric, knowledge was structured as poetry and dialoguesubject to interruption, questioning, and parenthetical diversions. The space of early writing was likewise flexible. Texts were ongoing affairs, amended by readers, revised by disciples; a forum for discussions. When scripts moved to the printed page, the ideas they represented became monumental and fixed. Gone was the role of the reader in forming the text. The unalterable progression of ideas across pages in a book gave the work an impressive authority-"authority" and "author" deriving from a common root. As Bolter notes, "When ancient, medieval, or even Renaissance texts are prepared for modern readers, it is not only the words that are translated: the text itself is translated into the space of the modern printed book."

A few authors in the printed past tried to explore expanded writing and thinking spaces, attempting to move away from the closed linearity of print and into the nonsequential experience of hypertext. James Joyce wrote Ulysses and Finnegan's Wake as a network of ideas colliding, crossreferencing, and shifting upon each reading. Borges wrote in a traditional linear fashion, but he wrote of writing spaces: books about books, texts with endlessly branching plots, strangely looping self-referential books, texts of infinite permutations, and the libraries of possibilities. Bolter writes: "Borges can imagine such a fiction, but he cannot produce it....Borges himself never had available to him an electronic space, in which the text can comprise a network of diverging, converging, and parallel times."

I live on computer networks. The network of networks-the Internet-links several millions of personal computers around the world. No one knows exactly how many millions are connected, or even how many intermediate nodes there are. The Internet Society made an educated guess in August 1993 that the Net was made up of 1.7 million host computers and 17 million users. No one controls the Net, no one is in charge. The U.S. government, which indirectly subsidizes the Net, woke up one day to find that a Net had spun itself, without much administration or oversight, among the terminals of the techno-elite. The Internet is, as its users are proud to boast, the largest functioning anarchy in the world. Every day hundreds of millions of messages are passed between its members, without the benefit of a central authority. I personally receive or send about 50 messages per day. In addition to the vast flow in individual letters, there exist between its wires that disembodied cyberspace where messages interact, a shared space of written public conversations. Every day authors all over the word add millions of words to an uncountable number of overlapping conversations. They daily build an immense distributed document, one that is under eternal construction, constant flux, and fleeting permanence. "Elements in the electronic writing space are not simply chaotic," Bolter wrote, "they are instead in a perpetual state of reorganization."

The result is far different from a printed book, or even a chat around a table. The text is a sane conversation with millions of participants. The type of thought encouraged by the Internet hyperspace tends toward nurturing the nondogmatic, the experimental idea, the quip, the global perspective, the interdisciplinary synthesis, and the uninhibited, often emotional, response. Many participants prefer the quality of writing on the Net to book writing because Net-writing is of a conversational peer-to-peer style, frank and communicative, rather than precise and overwritten. [...]

Distributed text, or hypertext, on the other hand supplies a new role for readers-every reader codetermines the meaning of a text. This relationship is the fundamental idea of postmodern literary criticism. For the postmodernists, there is no canon. They say hypertext allows "the reader to engage the author for control of the writing space." The truth of a work changes with each reading, no one of which is exhaustive or more valid then another. Meaning is multiple, a swarm of interpretations. In order to decipher a text it must be viewed as a network of idea-threads, some threads of which are owned by the author, some belonging to the reader and her historical context and others belonging to the greater context of the author's time. "The reader calls forth his or her own text out of the network, and each such text belongs to one reader and one particular act of reading," says Bolter. [...]

The total summation we call knowledge or science is a web of ideas pointing to, and reciprocally educating each other. Hypertext and electronic writing accelerate that reciprocity. Networks rearrange the writing space of the printed book into a writing space many orders larger and many ways more complex than of ink on paper. The entire instrumentation of our lives can be seen as part of that "writing space." As data from weather sensors, demographic surveys, traffic recorders, cash registers, and all the millions of electronic information generators pour their "words" or representation into the Net, they enlarge the writing space. Their information becomes part of what we know, part of what we talk about, part of our meaning.

At the same time the very shape of this network space shapes us. It is no coincidence that the postmodernists arose in tandem as the space of networks formed. In the last half-century a uniform mass market-the result of the industrial thrust-has collapsed into a network of small niches-the result of the information tide. An aggregation of fragments is the only kind of whole we now have. The fragmentation of business markets, of social mores, of spiritual beliefs, of ethnicity, and of truth itself into tinier and tinier shards is the hallmark of this era. Our society is a working pandemonium of fragments. That's almost the definition of a distributed network. Bolter again: "Our culture is itself a vast writing space, a complex of symbolic structures....Just as our culture is moving from the printed book to the computer, it is also in the final stages of the transition from a hierarchical social order to what we might call a 'network culture.'" [...]

The ever insightful Bolter writes, "Critics accuse the computer of promoting homogeneity in our society, of producing uniformity through automation, but electronic reading and writing have just the opposite effect." Computers promote heterogeneity, individualization, and autonomy. [...]

Swarm-works have opened up not only a new writing space for us, but a new thinking space. If parallel supercomputers and online computer networks can do this, what kind of new thinking spaces will future

technologies-such as bioengineering-offer us? One thing bioengineering could do for the space of our thinking is shift our time scale. We moderns think in a bubble of about ten years. Our history extends into the past five years and our future runs ahead five years, but no further. We don't have a structured way, a cultural tool, for thinking in terms of decades or centuries. Tools for thinking about genes and evolution might change this. Pharmaceuticals that increase access to our own minds would, of course, also remake our thinking space.

One last question that stumped me, and halted my writing: How large is the space of possible ways of thinking? How many, or how few, of all types of logic have we found so far in the Library of thinking and knowledge?

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, pp. 569-574)

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Writing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991.

A marvelous, overlooked little treasure that outlines the semiotic meaning of hypertext. The book is accompanied by an expanded version in hypertext for the Macintosh. I consider it a seminal work in "network culture."

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 587)

Gleick, James. Chaos. Viking Penguin, 1987.

This bestseller hardly needs an introduction. It's a model of science writing, both in form and content. Although a small industry of chaos books has followed its worldwide success, this one is still worth rereading as a delightful way to glimpse the implications of complex systems.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 596)

While that's always been true of books that intended to be topical, it is doubly true in these Internet days, and triply true of writing about the Internet or the latest take on scientific theories of mind, matter, and cosmic mayhem - writing, that is, in BOOK FORM in the era of the rapid electronic dissemination of data, one-to-one and one-tomany. Despite the coming of e-books since Kelly penned this print-text tome, books are still embedded in the cultural matrix of the technologies that created them and made them portable and cheap. That may be changing too, and fast, oh fast, but the logistics of publishing in print still lengthens the process by which ideas are filtered onto paper pages. By the time those ideas make their way into the bookstore, they are often dated.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 618)

For all his executive editing of Wired and immersion in that new world, Kelly chose to write Out of Control as a book. Nearly of his references to others' ideas are to books, magazines, journals, i.e. the world of text that formed him and in which he still lives and moves and has his very being. Well, it takes one to know one. I am a middle-aged man who began writing short stories as a teen and taught English literature at the University of Illinois in my twenties. I too span a divide between worlds that we can only see so clearly because we are a bridge generation. But this side of the divide, a different generation, socialized into the world we knew only by contrast with the one in which we were born and raised, speaks a completely different language.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, p. 619)

I hope this little reflection does not sound critical of Kevin Kelly's fun book, which is a wide-ranging compilation of interviews, ideas, and then-current techno-fashionable words. Writing a book like Out of Control as anything other than an encyclopedia or "road trip" of the inquiring mind was simply not possible. Because of what "writing a book" means. The book was congruent with the best efforts of a lively inquiring mind to surf the intellectual currents it hoped to understand, so it had to lack perspective. How can a book about this kind of non-book reality not lack perspective? The larger pattern it sought to discover or create did not yet and does not yet exist, and Out of Control did not finish the job so much as show us how difficult the task of self-definition during a transitional era really is. If the "book" or digital form that finishes that task does exist, it is being written by someone else whose genius has not yet been recognized. But then ... the whole notion of a piece of "intellectual property" written by "an author" rather than a collective identity into which our "individual identities" merge (and individual identities like individual rights are only a few hundred years old) ... that's a wistful romantic idea that evokes nostalgia from those who are increasingly embedded in the wireless and wired network that is turning us all into nodes with names assigned dynamically, on the fly, rather than named forever at an arbitrary moment of birth. Our second birth, said Carl Jung, is our own creation, and one can't fault Jung either for not knowing that humanity would soon have the opportunity to choose identities for a third birth, a fourth birth and many more as longevity stretches toward 150, 175, even 200 years and the life span of a tortoise brings social challenges we can not even think yet to

our long-term memory storage devices, our sense of the persistence of a single self, and what in fact we decide it means to be a human being. [...]

We can only know that which the knowing of which no longer threatens our identities or selves with annihilation. The new paradigm is only grasped after the shock of change has been absorbed and we sit up again, rubbing our heads, looking out at the landscape with wonder. It was fun to visit these ideas, people, and places once again, like any nostalgic road trip is fun, and a little wistful and melancholy. We know at the end of the trip that the most we can know is how a wave might break as it gathers momentum and the most we can do is surf the wave and enjoy the ride, breathing the ozone at the edge of the curl of consciousness trying to understand whole an impossible collection of fragments. That is a challenge we can't seem to resist writing books like "Out of Control," knowing our inadequacy to the task of defining the Bigger Picture. Crawling like miners with lamps on their hats through a long tunnel in the vast mountain of darkness, looking at the square foot of illuminated earth in front of our faces and thinking we see where we're going, our audacity more than equal to Kelly's in writing that book, i.e. writing a review like this only six years later and pretending that everything in the past, although obviously as much a mystery as the present and the future, can be somehow understood.

(Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. Reading, MA: Perseus Press, 1995, pp. 623-625)

.jpeg)

Commenti

Posta un commento